The Vending Machine Problem

On the future of AI in physical spaces

Michael - February 2026

In April 2020, the New York Times built an interactive model to predict when we'd get a COVID vaccine. The journalists did rigorous work. They interviewed vaccine experts, studied historical timelines, and built a simulation with adjustable variables. Their "realistic" estimate was November 2033. Even with every optimistic assumption toggled on, the model couldn't produce an answer earlier than 2023.

The actual answer was April 2021.

Alexandr Wang, CEO of Scale AI, uses this as the centrepiece of his argument about predicting the future. He wrote it in 2021, when Scale was valued at around $7 billion. Since then, the company has become the data infrastructure behind OpenAI, Meta, Google, and the US Department of Defense - valued at $29 billion, with Wang becoming the world's youngest self-made billionaire along the way. He's clearly made a few correct calls. The model wasn't wrong because it was a bad model. It was wrong because mRNA technology - experimental, unproven, and excluded from every reasonable forecast - was about to work. You can't really model that.

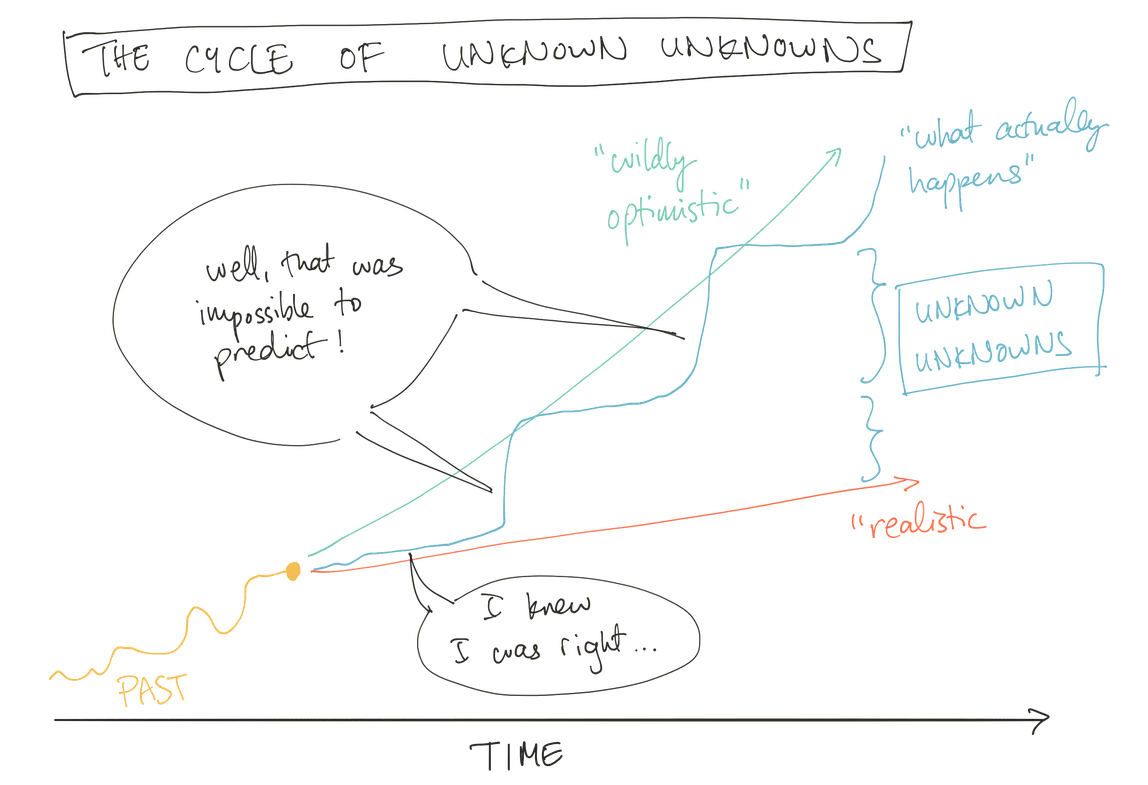

This keeps happening. Wang calls them unknown unknowns: breakthroughs you can't name in advance but that, in retrospect, were almost inevitable. Moore's Law has survived for sixty years - and nobody in 1965 could have described the specific engineering innovations that would sustain it. Betting against human invention has just been, on the whole, a terrible bet. The experts who declared Moore's Law dead were being realistic. They were also wrong. Again.

The lesson can be that optimism beats pessimism if you like, but It's mainly that the confident extrapolation - the prediction that extends today's trajectory forward with reasonable assumptions - is usually the wrong bet. The future doesn't extrapolate logically. Or does. We just never have all the variables. Which, in practice, amounts to the same thing.

The path of most confidence

Right now, the confident extrapolation in AI goes something like this: AI models get better, cheaper, faster. Software eats more of the world. The companies that win are the ones building agents, copilots, and digital infrastructure. The interface is the screen.

This isn't a bad prediction. It's probably partially right. But it has the same structural flaw as the vaccine model - it extends the current trajectory and assumes the variables that matter are already visible. It might not even be actively chosen because it's being predicted. It might just be the path of least resistance - the done thing, inseparable from an AI play, the default shape a startup takes when it says "we're doing AI." It doesn't really matter why. Software companies keep on bloody coming.

Peter Thiel's most famous question is: what important truth do few people agree with you on? Today, I'm defending the future of brick and mortar companies. I think the next interface revolution might not happen on your phone or your laptop. I think it might happen on the high street, and I think almost nobody is taking that seriously.

Not robots. "Robots will do our dishes" is a known unknown - an extrapolation from what exists. We have robots, we'll get better robots, they'll handle more tasks. That might be true, but it's not interesting. The interesting question is what nobody's imagining yet. The interesting question is what shows up in physical space and restructures our relationship with it the way the iPhone restructured our relationship with information.

My parents didn't predict the smartphone. They knew phones were improving. But they didn't know a device was coming that would reorganise commerce, entertainment, navigation, relationships, and their own attention spans. They couldn't have known, because that's not what phones were for. The iPhone wasn't a better phone. It was a new interface to everything.

We don't predict interface revolutions. One day you just wake up with a screentime of 10 hours and 15 candy crush notifications.

Economically...

Every AI software company on earth is burning cash to solve the same problem: distribution. How do you get users? How do you keep them? How do you make them pay? The entire growth-hacking, ad-buying, retention-optimising machine exists because software has no natural habitat. It has to manufacture attention every day.

Physical spaces have already solved this innately. Gyms have members who show up three times a week. Shops have foot traffic. Clinics have patients who return. Salons have regulars. These businesses have something software startups kill for: habitual, repeated, in-person engagement with paying customers who already trust them.

Point being, as much as the high street sentimentally has charm, its also got clear economic advantages. Physical spaces are undervalued AI distribution infrastructure.

The assumption embedded in most tech/social discourse is that physical retail is dying - that digitalisation is a one-way process culminating in something like a metaverse, synthetic engagement overtaking real experience. Consider, what if physical spaces don't die at the hand of software? Maybe they absorb it. What if the next medium isn't an app but a building?

The design problem nobody's solving

This is where it gets genuinely hard, and genuinely interesting. Because the design problem of AI in physical space is completely different from AI on a screen.

Cafe X, a robot barista startup in San Francisco, made great coffee cheaper than anyone else in the city - and still couldn't win customers from traditional coffee shops. They closed all three downtown locations. The ones with seating areas went first. They survived only in airports, where nobody wants an experience and everyone just wants caffeine before their gate. The robot works where the space doesn't matter.

That's the whole problem in miniature. A cafe with a brilliant AI system that takes your order, remembers your preferences, and optimises the menu is potentially a better cafe. A cafe with an AI vending machine where the barista used to stand is clinical, and dystopian - and has proven to reduce sales, even though the technology is sound. Same capability. Same Coffee? Completely different experience.

I think about the ROI pitch a lot - you're cutting costs, increasing efficiency, the CFO's starting to twitch. But that tension between integration and alienation is probably going to be one of the most important branding problems of the next decade, and it's going to take genuinely thoughtful people to get right. People who understand that a shop is an experience before it's an optimisation problem. (I guess UXers)

Think about a gym. You scan in with a QR code on each machine. Sensors in the equipment track your movement, an AI translates that data, and guides you: form correction, load recommendations, long-term programming. Not an app you check between sets - but the gym itself, aware of what you're doing, helping you train better. It knows what you lifted last week. It tells you to add five kilos or back off. Your training plan adjusts as you go. Wearables like WHOOP have some of the craziest ARR you'll see because people like to see their progress. And the physical gym can extract better data than just your heart rate. Why doesn't the physical establishment take market share?

Do the same with fitting rooms - mirrors that show you in different sizes without changing clothes, and style recommendations based on your actual body. Do the same with salons and haircuts.

And every single one of these could go wrong. Could make the gym feel clinical. Could make the fitting room feel surveilled. Or not. The same technology produces either outcome depending entirely on how it's designed, how it's introduced, what it looks like in the room. That's a product problem. And it's the kind of product problem that barely anyone is working on because the talent is all in software.

Visible or invisible

There's a version of all this that goes badly. Where it's just screens bolted onto everything. That's the vending machine cafe at scale. And that version is what most people picture when they hear "AI on the high street" - which is partly why nobody takes it seriously.

But the people who get this right will understand that the AI should probably be invisible. The best technology in a physical space is technology you forget is there. It just makes the place work better, the way good lighting or good acoustics do.

So we can extrapolate, easily, that AI can integrate into physical spaces. But the question is whether the integration feels like infrastructure or intrusion. Visible or invisible. And that question is almost entirely unanswered because the people building AI are building software, and the people running physical spaces aren't thinking about AI.

If I was Black Rock, I'd have a look in that gap.

Betting on where nobody's looking

Wang makes a crucial distinction about where to place these bets. You can only bet on unknown unknowns near the frontiers of tenacity and creativity. A struggling department store chain probably doesn't have the density of obsessive, creative people who generate unexpected breakthroughs. You bet on the people, not the sector.

Right now, the obsessive and creative people are almost entirely in software. Foundation models, agents, digital infrastructure. The physical world is an afterthought. The number of seriously talented people thinking about how AI reshapes a building, a street, a shopping experience - it's small. And there are obvious reasons for that. Physical retail is fragmented, margins are thin, hardware is expensive, and there's no standardisation - none of the clean, scalable abstractions that make software so attractive to work on. But I guess that's exactly the point. Those are the conditions that repel confident extrapolations. They're also the conditions that become a moat if someone figures it out.

That's either a sign that it's a bad idea, or a sign that it's early. The confident extrapolation says it's a bad idea. But the confident extrapolation is usually wrong.

I want to be precise about what I'm arguing and what I'm not. I'm not arguing that I know what AI on the high street looks like. I don't. The gym, the fitting room, the cafe - these are probably the wrong examples. If history is any guide, the actual breakthrough will be something none of us are currently imagining. These are the known unknowns, the reasonable extrapolations. The unknown unknown will be the thing that makes all of this feel as quaint as the nokia brick.

But I think the direction's right. The economics point somewhere. Physical spaces aren't going away - people still want to be somewhere. The design problems are fascinating and unsolved. And if you believe Wang's framework - that unknown unknowns cluster near underinvested frontiers - then physical AI is worth paying attention to. I think there's a massive company waiting to be built in integrating AI into the world's retailers.

The loudest prediction right now is that AI is a software revolution. It likely is and isn't depending on the length of your y axis. But the loudest prediction is also, by definition, the one most likely to be the known unknown rather than the unknown one.

The future tends to show up where nobody's looking. Right now, nobody's looking at the high street.