Less Is More in Design. When Will We Need to Artificially Give More Back?

Michael - December 2025

Simple products will win. This feels like an obvious conclusion to arrive at. Because currently, products that do the most for the least are the most technologically impressive. That's the x and y of our moment: maximum output, minimum input. Reduce friction. Have the thought for the user. Propose only the essentials. Do it all.

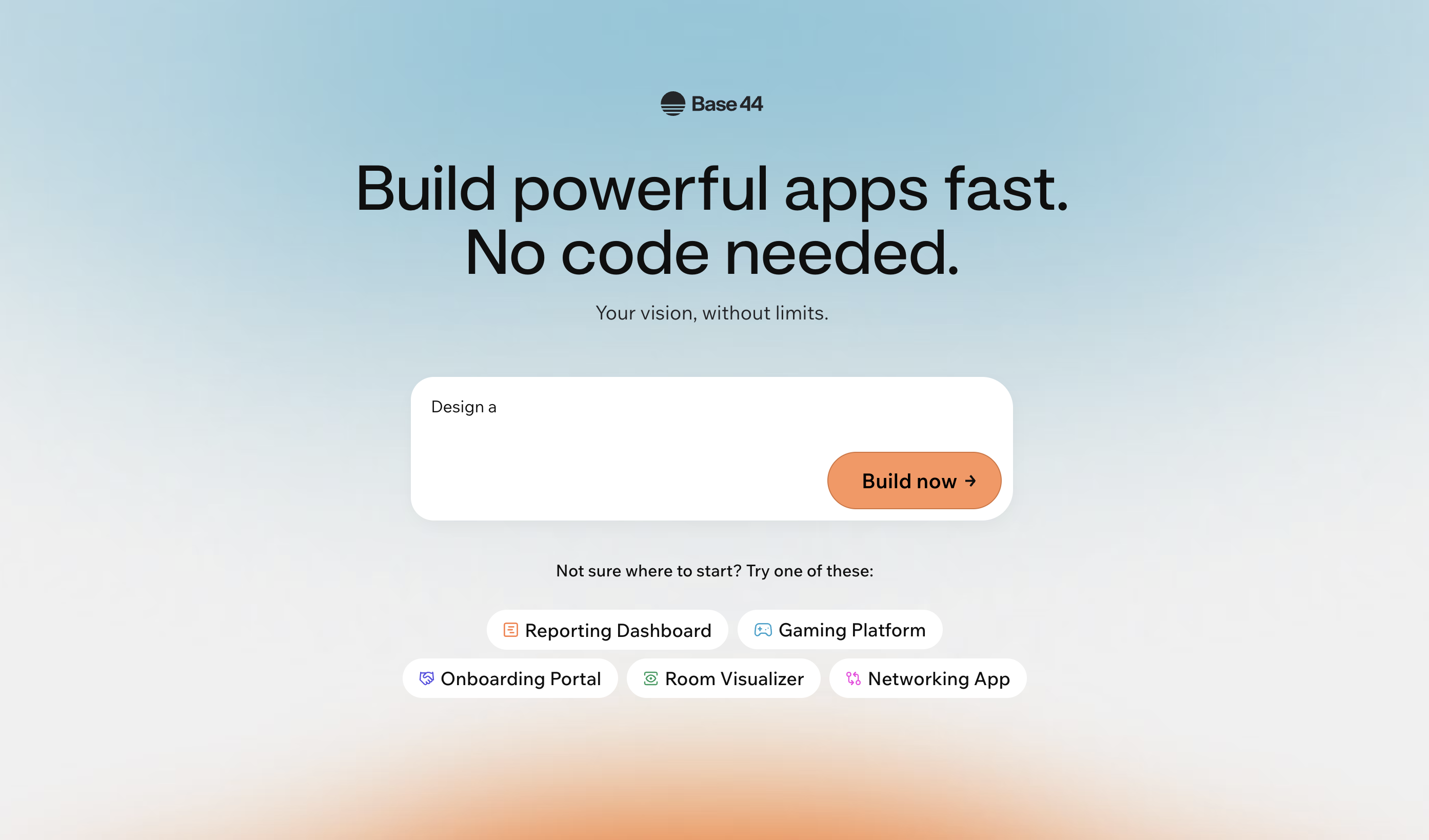

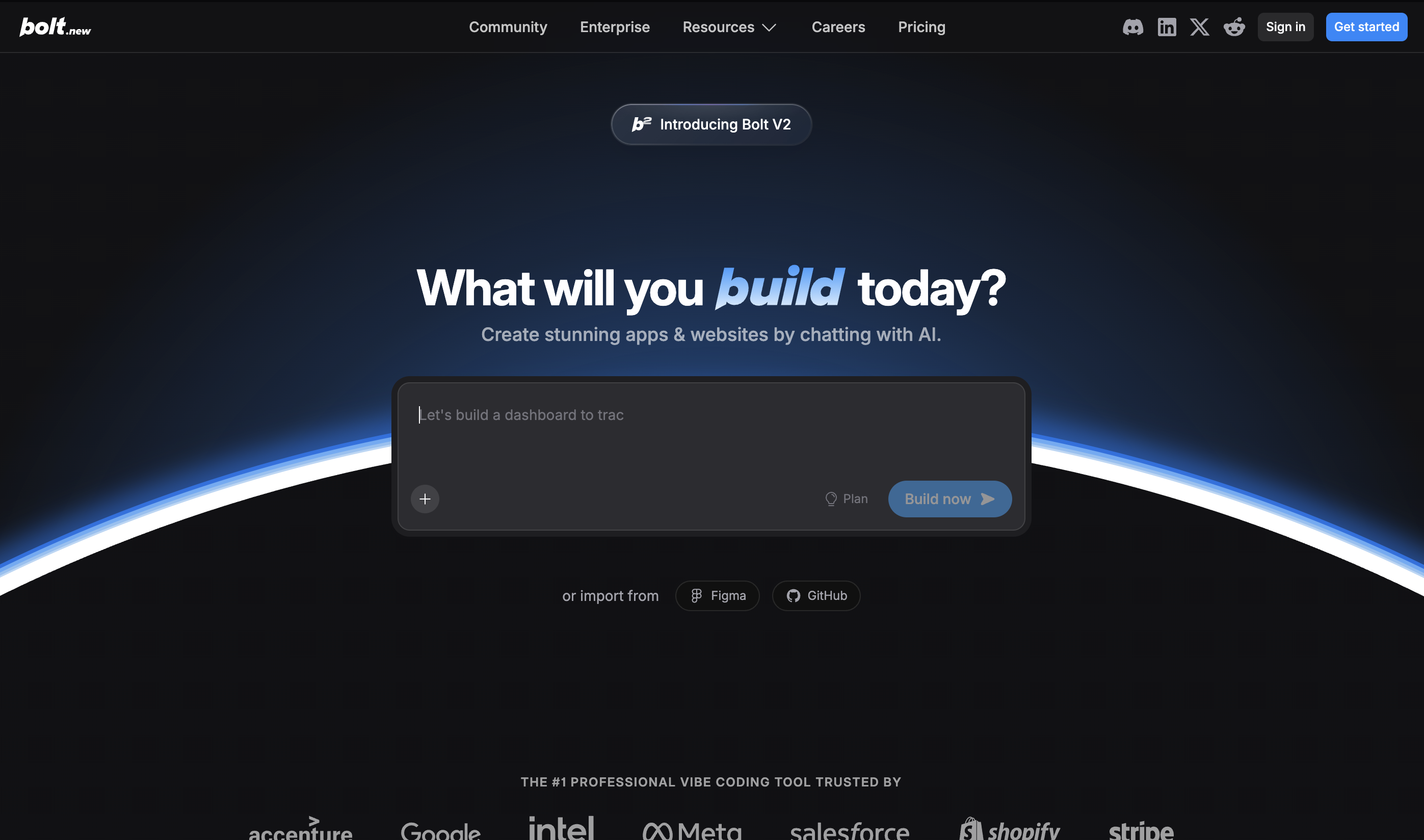

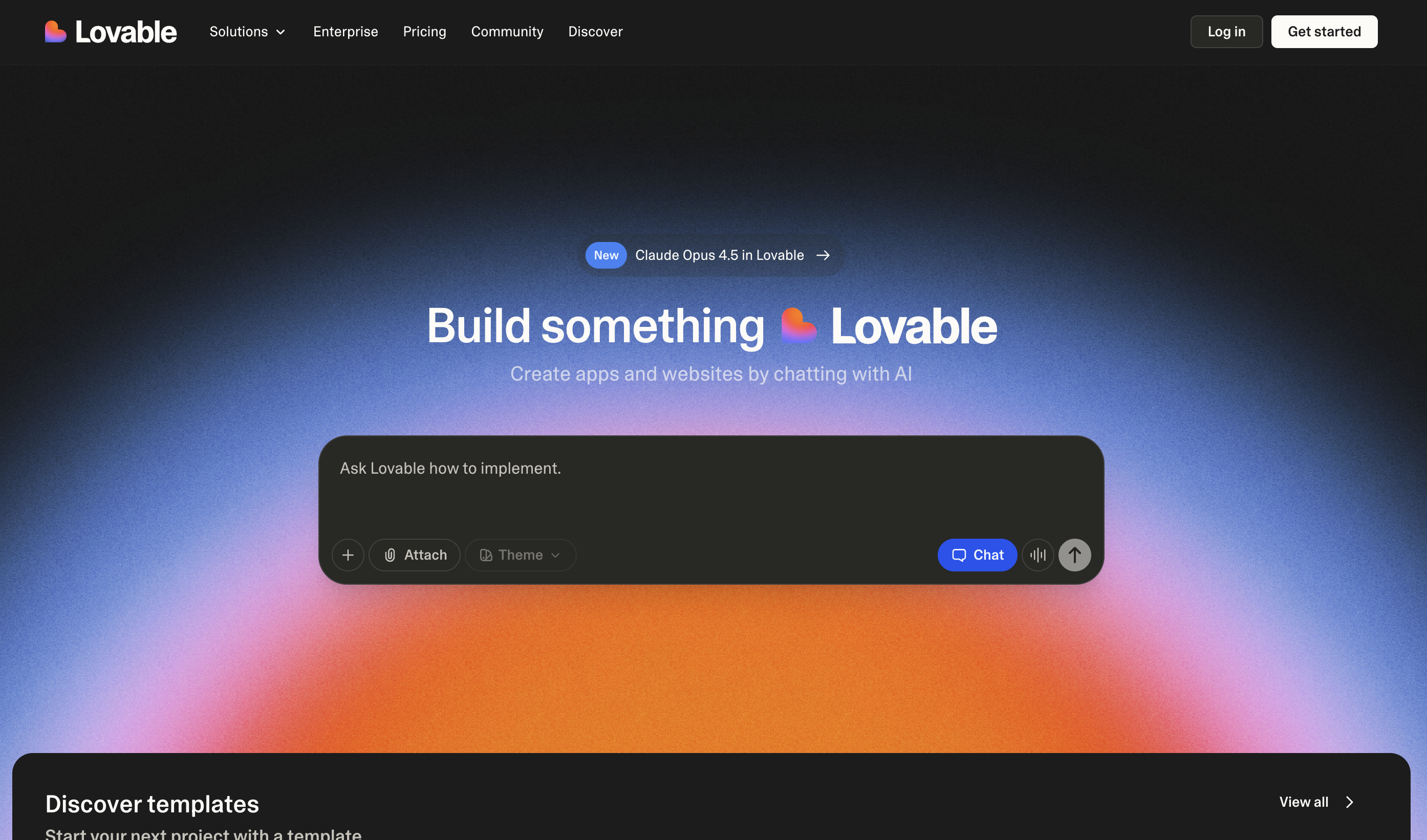

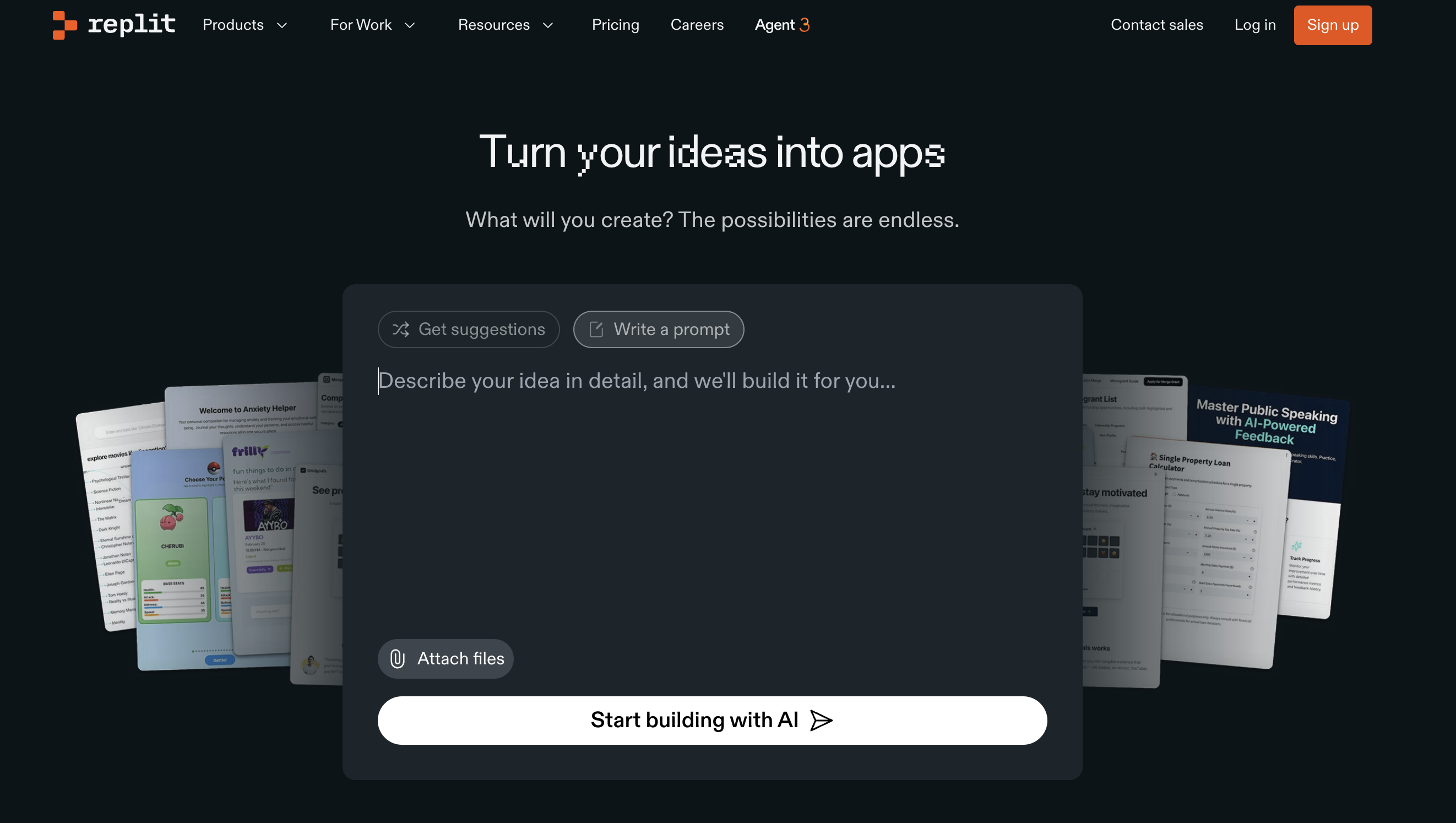

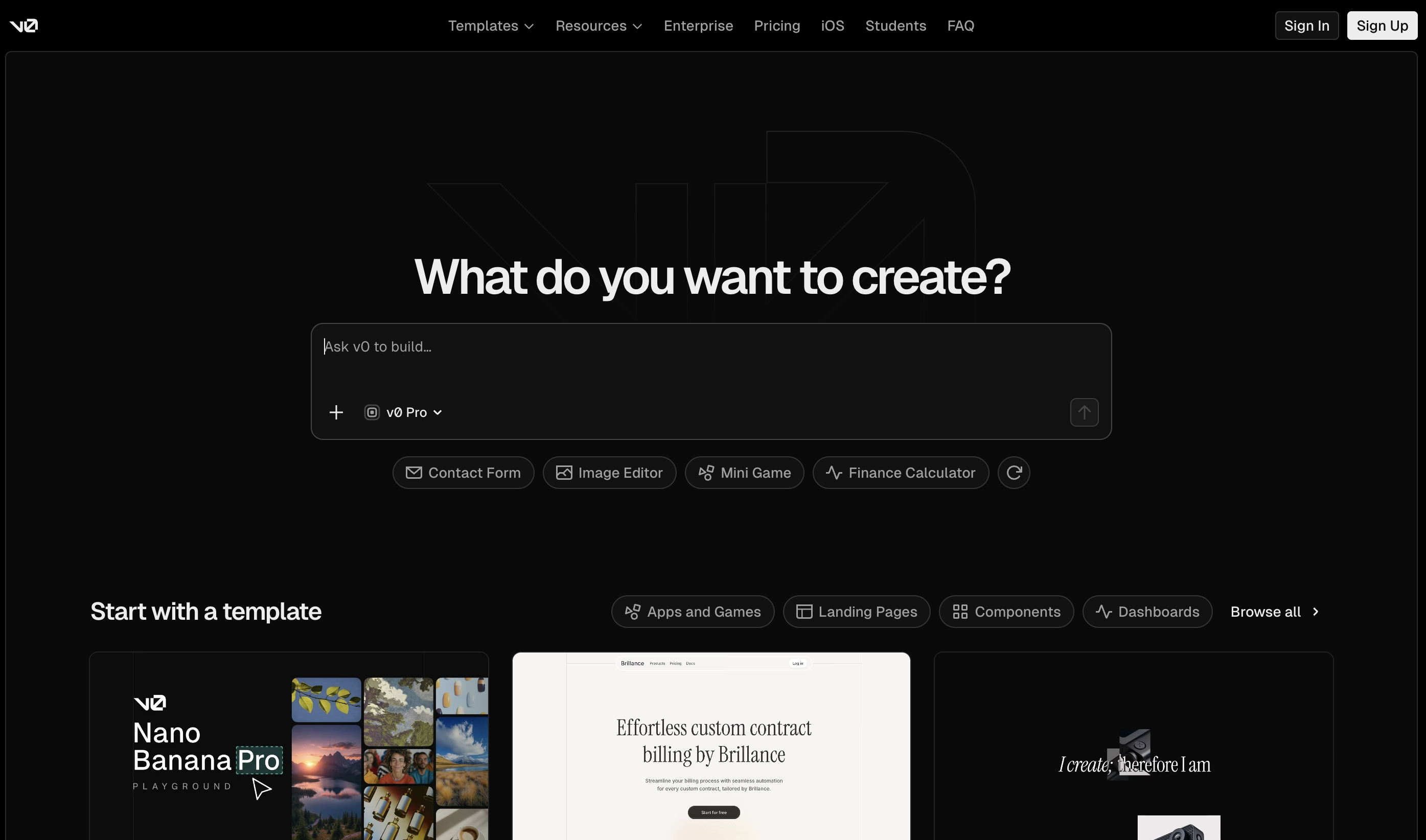

This is why we've seen a massive influx of landing pages with nothing but a title and a text box. Type here to bring your imagination to life-with generative AI hiding behind it, implied but hidden.

That's the target of all great design teams today. And i guess it probably should be too.

But I suppose the interesting question is what happens when everyone gets there? and what comes next for design?

The Return of More

When every product can do everything from a single input — what differentiates you? Either as a differentiator competitively, or as a psychological phenomenon, i think complexity will come back.

Not because the AI can't handle it. But because people might actually want to have a say in their outcomes — regardless of whether it inhibits objective quality. How else can it feel like it'stheirs?

I think the best analogy is the IKEA Effect. People value what they build more than what they're given, even when the given is objectively better. Norton, Mochon, and Ariely demonstrated this in 2012 — participants valued their own amateur origami nearly as highly as expert work. The complexity was the thing they liked. They liked it because they were there.

Ignoring that an inexorable meaning crisis that is definitley coming in 10-5 years. If the model writes your report, designs your presentation, codes your app-where do you exist in the result? Where's the mark you leave? At what point does "your" work become indistinguishable from everyone else's, because you all used the same frictionless process?

Operator → Orchestrator → Observer → ?

Right now, the discourse frames the shift as users moving from operators to orchestrators. A16Z's piece on agency by design captures this well: you set initial parameters, then step back as the system runs itself. Your role becomes supervisory, not interactive.

But that's the current phase. What comes after orchestration?

When AI systems get good enough, you won't need to set parameters. You won't need to supervise. The machine will know what you want before you articulate it-or it'll produce something better than what you would have asked for anyway. Orchestration becomes unnecessary.

At that point, you're not even in the loop. You're an observer of outputs that bear no trace of your involvement.

The Moderator's Privilege

Here's the thing: you can only moderate from a position of knowing more. That's the current justification for human-in-the-loop systems. The Human-in-the-Loop (HITL) literature — work from Stanford HAI, IBM, and others—frames human involvement as quality assurance: catching errors, providing ethical oversight, handling edge cases the model can't.

Google's design team calls this navigating the "simplicity-control spectrum." They note that even products optimised for simplicity still surface controls-sliders, settings, manual overrides. The peace of mind that comes from being able to take control matters, even if you rarely exercise it.

But this framing assumes humans have something the machine doesn't: context, judgment, domain knowledge. What happens when that asymmetry disappears?

The moderator's privilege is predicated on knowing more than the thing you're moderating. When you don't, there's no reason for you to be there-functionally speaking.

But functionally isn't the whole story.

I want complexity back

The HITL literature focuses on when humans should intervene — for safety, accuracy, ethics. That's a functional argument.

The IKEA Effect suggests something different: humans might want to intervene regardless of whether they're needed. Not because the output is worse without them, but because their absence from the process makes the output feel less theirs.

This is where the existing discourse has a gap. Most writing on human-AI interaction treats complexity as something to be managed or balanced-see Tesler's Law, which states that complexity can't be eliminated, only shifted. Simplify the interface and you push the complexity to the backend, the AI, the designer.

But what if complexity isn't just something to be managed-but something to be offered? Not friction for friction's sake. Not gratuitous difficulty. But meaningful engagement points. Places where humans insert themselves into the loop-not because the machine failed, but because they wanted to be there.

Complexity as Personalisation

Truthfully, I have concerns we'll lose complexity completely as a sacrafice for mass markets. But it's also possible and perhaps likely that complexity will become a scale to personalise toward specific audiences:

Those who still want to give their brain a run-out - the hobbyists. They'll pay for tools that let them participate deeply, not just prompt and receive. Like how we play chess, even with chess engines for the better part of 20 years being easily accessible and unbeatable.

Those who want to leave a mark on their outputs—professionals whose identity is tied to their work, who need their fingerprints visible in the final product. Sit in the cockpit and see all the buttons but only really ever need to push a handful. Someone who's pride comes from knowing how to drive the plane.

And those who don't really mind — who'll speak anything into existence in a few years, and then think it once AI gets into our brains. The mass market, I suppose. Those who we're making it convienient for.

The future might not be simpler tools. It might be tools that know when to unfold-and trust you with what they reveal.

Right now, good design teams show you everything, then hide it. They surface complexity in the moment of decision, then collapse it once you've chosen. The complexity is there, but it's purposefully fleeting.

What happens when people want it to stay?

Less is more. Until more is what you're missing.